Click here for iFriendly audio.

Ross Coen was a professor of at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks for 10 years. He’s also a research associate Museum of the North and a first year Ph. D. student in history in Washington.

Here’s his story of the 1937 Bristol Bay Salmon Crisis when Japanese fishermen entered Alaskan waters as told to KSTK reporter Shady Grove Oliver…

The time is July 7th, 1937. Tensions are brewing in Europe and America is waiting to see if a second world war will break out.

The Japanese have invaded Manchuria and war is beginning between China and Japan. Across the Pacific Ocean, Alaskans are wondering what will happen next.

“Japanese imperialism was on the rise. That was very clear. And consequently, American fear and anxiety about exactly what was going to be happening in the Pacific and how Alaska might be drawn into that conflict was very much on Alaskans’ minds,” said Coen.

Coen said, at that time, another conflict is brewing in the waters of Bristol Bay.

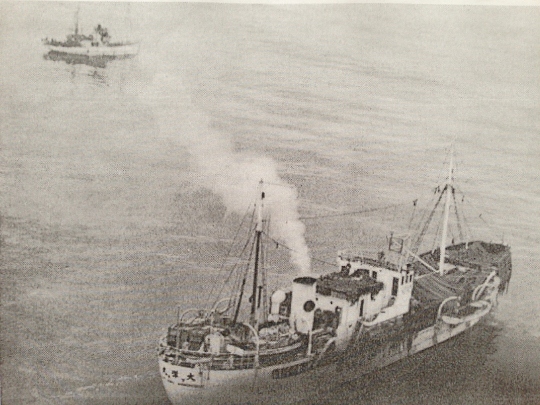

It’s hard to know exactly how many vessels entered Alaskan waters that week, but it may have been as many as 30.

“Now this is about four or five large processing vessels—what they called floating canneries. These were ships that had processing and canning facilities right there on board the vessel. And then there were probably another couple dozen smaller trawlers that used gillnets to harvest the salmon which were then transferred onto these motherships,” said Coen.

In the 1920s, fisheries off of Japan were declining. So they moved to Kamchatka, a Soviet territory they had access to after the Russo-Japanese war of 1904. Those were in decline as well.

“And so the Japanese moving into the eastern Bering sea, coming into Alaska waters, was really a function of—they had already over fished their home fisheries and now they came into Alaska thinking this was a fishery that they might find productive and economical,” said Coen.

At that time, the Fisheries Bureau prohibited the use of motorized vessels, fish traps, and purse seins in Alaska. This was to ensure a 50% escapement of the spawning salmon to guarantee sustainability of the resource.

This means the Alaskan fishermen were working on wooden vessels with 900 foot maximum length gillnets.

“But now you have these 10,000 ton, steel Japanese vessels that are diesel-powered. They’re operating gillnets two, possibly even 3 miles in length. I mean, it was such a technological mismatch in favor of the Japanese, that you’re exactly right, it proved intimidating and it really fed Alaskans’ feelings of resentment,” said Coen.

Coen said there had been a long-standing tension between resident Alaskan fishermen and the salmon canneries based in Seattle and San Francisco.

“But yet, when the Japanese enter Bristol Bay and threaten to extinguish the salmon fishery, all of a sudden, you’ve got common cause between Alaskans and people in the lower 48. And it really aligned their interests in a way. And that hadn’t quite happened before,” said Coen.

In 1938, the United States came to an agreement with Japan that the Japanese would refrain from fishing in Alaskan waters. This agreement was honored until Japan and the United States entered WWII following the incident at Pearl Harbor.

However, it came up once again, more than a decade later.

In the 1950s, Japan was once again strengthening its fishing presence in the Pacific. In 1953, The US, Canada, and Japan passed the North Pacific Fisheries Treaty in which the region’s resources are jointly managed by the three countries. This treaty is the model for international fisheries regulations today.

Coen said the Bristol Bay Salmon crisis was the first time questions of international fishing boundaries really came to light.

“I mean for many, many years, Alaskan fisheries were essentially secure simply by virtue of the fact that no other nation had the technological capability to enter the fishery and then economically harvest those fish. When the Japanese proved it could be done, in 1937, it was, in many ways, the start of these questions that we’re still dealing with today,” said Coen.

He said that’s just one of the many legacies of the 1937 Bristol Bay Salmon Crisis.

Coen is speaking Thursday, March 21, 2013 at 7pm at the Nolan Center for Wrangell’s Chautauqua series.