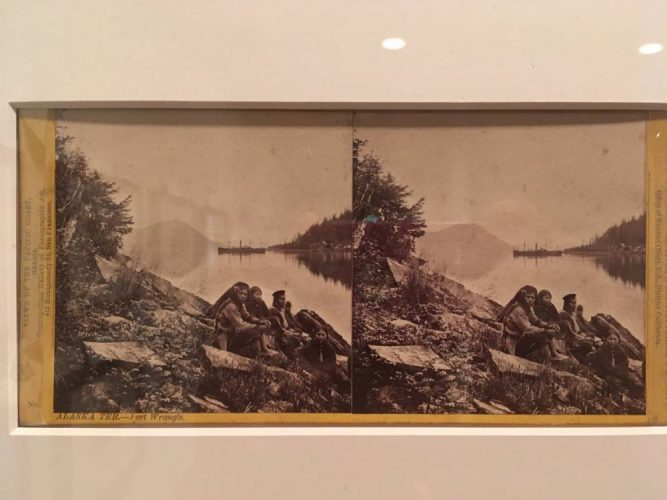

Alaska museums have been showcasing some of the earliest photographs ever taken in Southeast Alaska. A roving exhibit of Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs from the late 1800’s depicts the region in a time of flux.

At the exhibit’s opening in Wrangell’s Nolan Center, local Kate Thomas looks at one of the 16 photographs on display. But she has to use a viewfinder.

“I mean there’s depth to the photo. Layers. Like 3D layers.” she says.

The photos are called stereograms, because they’re pairs of images. Peering through the viewfinder takes in the side by side images at once, creating an almost 3D image.

“Kind of crazy that that could occur 150 years ago,” Thomas says.

The exhibit “1868: Muybridge in Alaska” gives folks an interactive taste of the evolution of photography. After all, photographer Eadweard Muybridge is considered the father of moving pictures, with his motion studies. If you’ve seen the famous 1878 photo series that proved a race horse does in fact lift all its legs off the ground in a gallop, that’s Muybridge.

But the exhibit is also a testament to the changes of the Southeast Alaska region. Muybridge came to Alaska one year after the U.S. purchase from Russia. An American general commissioned him to take pictures of military forts in Sitka, Wrangell and Tongass Island.

Exhibit curator Marc Shaffer says Muybridge took advantage of his trip to produce any photographs he could sell to the general public. That included landscape photos and portraits of native people.

Shaffer says he needed to get the Alaska Natives’ perspective on his work to better understand what was happening beyond the frame.

“The pictures capture a moment which is not very good for Tlingit people,” he says. “It wants to sever their own connection to their history.”

Alaska audiences first saw the exhibit in January at the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage. It also traveled to Haines, before coming to Wrangell. Considering Muybridge photographed Wrangell Island, Shaffer says the reactions of locals here is even more intimate.

“I kind of thought that some native people might really hate these photographs because it shows this moment. And I’ve been surprised at how much the native people love the photographs,” he says.

At the opening night, Shaffer projected one image for the crowd to reflect on. It’s where the industrial park is now, and before that the mill. The photo shows two totem poles in front of a plank house.

Virginia Oliver recognized Wrangell landmarks, currently held at the museum. She says it’s Lu Knapp and Sue Steven’s great grandfather’s house. That’s Chief Kadashan of the Kaasx’agweidi people.

Stevens stood up to speak. She confirmed that was her great grandfather’s house, and that he commissioned those totems. She enjoyed seeing the photo, but she wanted to explain to Shaffer what that time in history and beyond means to her.

“You said earlier that every time Americans or Europeans stepped on our land they claimed it. But we didn’t recognized them as our leaders. The Tlingits were never defeated by the English of Russians or the French. So I just wanted to say you can’t just come to our land and say that kind of stuff,” she says.

Funding for the exhibit came from the museums, the Atwood Foundation, the Rasmussen Foundation, and the Alaska humanities forum.

The exhibit’s final stop is in Wrangell’s Nolan Center. It’ll be here through August 31st. In Wrangell, I’m June Leffler.