(Courtesy of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources)

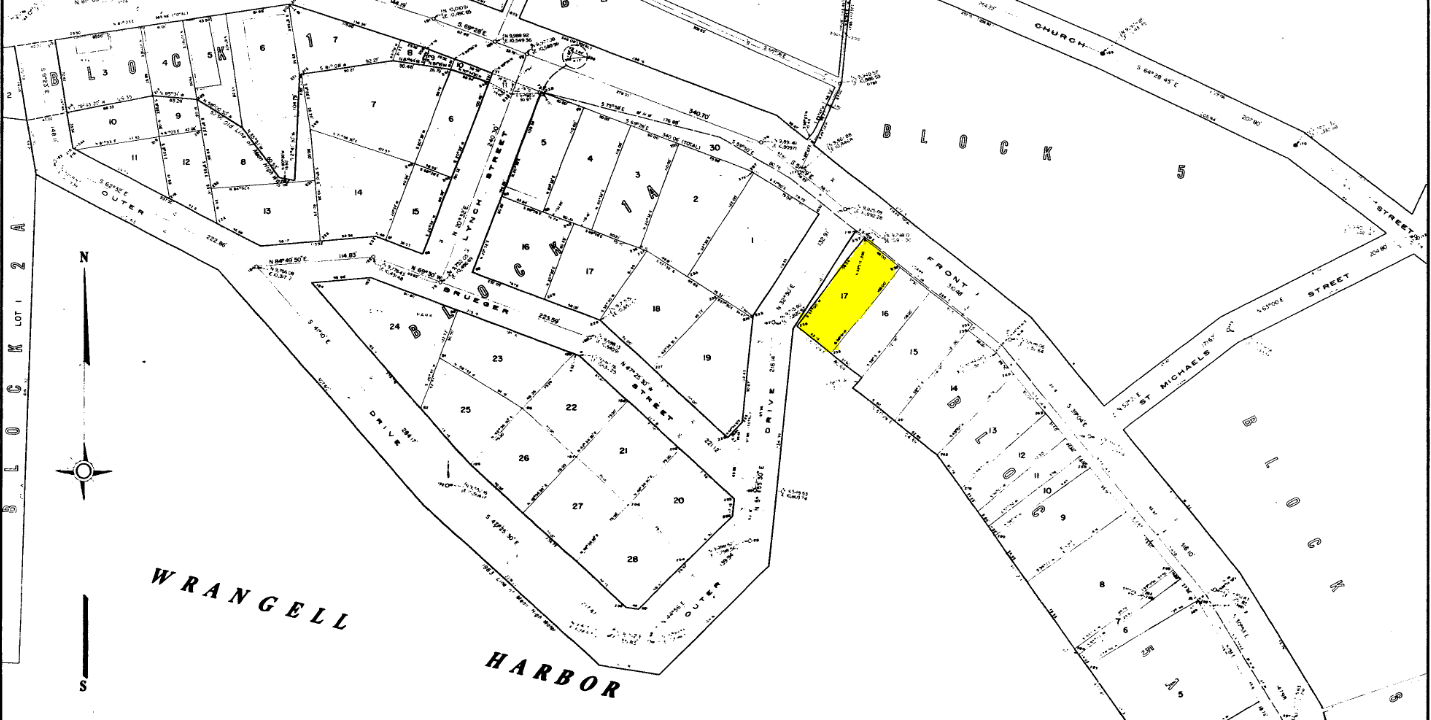

309 Front Street is an unassuming, 0.1-acre plot of nothing. Over the years, it’s housed a variety of businesses, including an auto shop. But all that’s gone — at least on the surface.

Under the surface, it’s contaminated by lead.

In 2011, the city bought the plot of land, which sits across the street from what is now Twisted Root Market, knowing that it contained underground fuel storage tanks, but not that those tanks were leaking.

(Sage Smiley / KSTK)

The three tanks were removed in the ensuing years, along with 45 cubic yards of soil. While those removals took care of the petroleum contamination, the city also discovered lead levels in the soil above DEC acceptable standards.

So it’s officially contaminated. But it’s also a piece of downtown real estate that the city wants developed. The local tribe, the Wrangell Cooperative Association, has reached out to the city to ask about making the site into a parking lot, as it sits next to the WCA cultural center, also known as the carving shed.

State regulators, though, won’t let anyone build anything until someone cleans up the lead-laden soil.

And that won’t come cheap — according to the cleanup assessment done by the environmental contracting firm Shannon & Wilson earlier this year, surveying and cleaning up the lead in the soil would cost around $65,000.

So who should pay? Ideally, the federal government.

The EPA runs a program called the Targeted Brownfields Assessment program that could offset that cost for the city.

The issue the city is running into is that in order to receive EPA assistance with the site, there can’t be any other financially viable responsible party. In other words, if any previous owners could potentially pay for the cleanup themselves, they could be on the hook. Borough manager Lisa Von Bargen put it this way at the assembly’s August 11 meeting: “The difficult but short summary here is, if we move forward trying to get EPA to do this assessment for us, we will be, I hate to use this term, forcing a financial viability review upon a previous owner of this property.”

Generally, this means looking back at all of the previous owners that could have potentially contaminated the property. According to Von Bargen, that’s four or five. The state of Alaska has records online for the two most recent owners:

In December of 1976, Zennie and Rachael Madden of Hoonah sold the lot to Charles and Nola Wilcox. Then in February of 2011, Nola Wilcox sold the property to the City and Borough of Wrangell for $42,100 dollars. By that time, Charles Wilcox had passed away.

Zennie and Rachael Madden are also deceased. Although they weren’t the ones that put the underground fuel storage on the property–the tanks were added in the 1980s, years after Charles and Nola Wilcox had already purchased the property–nobody’s quite sure where the lead came from.

In summary: because all other previous owners are dead, Nola Wilcox is the only possible heir to the liability for cleaning up the site — meaning she could be on the hook for that $65,000.

Manager Von Bargen added: “If that person is [found viable], not only will they be under a microscope for their finances, they will also if they’re found to be viable, financially viable in whole or in part, DEC, EPA may go after them to do that. But the other option is that the bureau says no to the program, and that our general fund money goes to pay for this assessment on our own.”

At the same meeting, the borough assembly was uncomfortable with just allowing the EPA free reign to contact Wilcox and examine her financial information. The assembly resolved to try and reach out on a more personal level to discuss the pickle.

But as of late August, Von Bargen reports the city hasn’t been able to get in contact with Wilcox, let alone received her permission for a DEC legal team to examine three years worth of her tax records to determine potential liability.

For now, then, 309 Front Street sits empty, unused, and contaminated.

Get in contact with KSTK at news@kstk.org or (907) 874-2345.