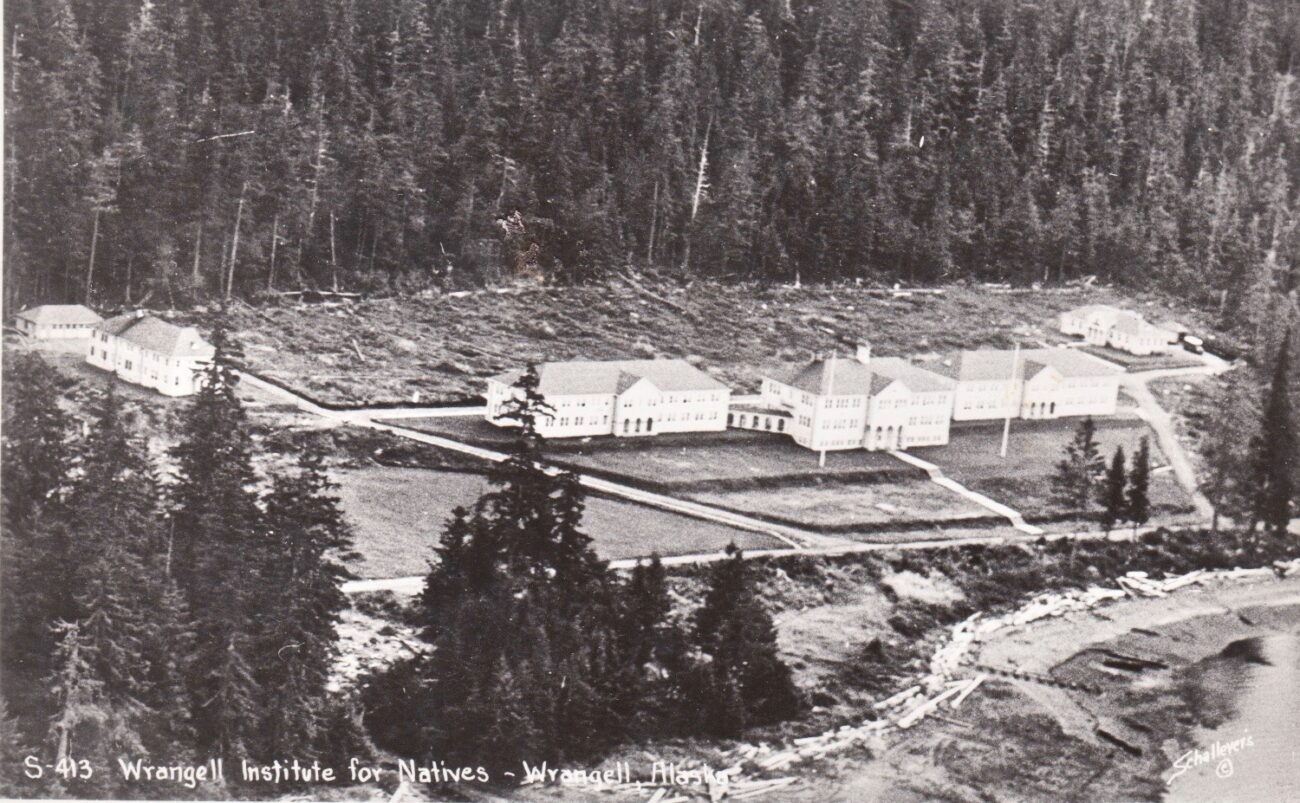

A government boarding school for Native children in Wrangell was one of the first of its kind in Alaska. Now, there are plans to redevelop the site of the former Bureau of Indian Affairs facility that was open for 43 years. But sensitivity towards the legacy of abuse and trauma and recent discoveries of graves at Canadian boarding schools have caused local officials to tread carefully before breaking ground.

After the Wrangell Institute closed in 1975, the former boarding school was sporadically used. It was transferred to Wrangell’s local government about 20 years later. There was some outside interest in using at least part of the site for another boarding school, but nothing panned out.

(Sage Smiley / KSTK)

Now, the Wrangell assembly is eying it as land for new housing, with a plan to subdivide the 134-acre property into residential lots. One of Wrangell’s borough assembly members ran for re-election this year on a platform of getting the former Institute Property developed and sold off.

But first, the city needs federal permits to fill wetlands. It applied earlier this year to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers after teeing up about $1.3 million towards redevelopment.

When the City and Borough of Wrangell applied in May for a wetlands fill permit to start developing the former Wrangell Institute property, the Army Corps of Engineers stated that it was unaware of any cultural resources at the site.

But days later, news broke of a grisly discovery in Canada: the remains of more than 200 Native children were found on the grounds of a former residential school in British Columbia. In the following weeks, thousands more bodies would be discovered at the sites of former residential schools across Canada, shedding light on the country’s dark history of mistreatment of Indigenous peoples. Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission has documented more than 6,000 Indigenous children’s deaths at Canadian residential schools, but estimates that 15-25,000 Indigenous children may have died at the schools.

Wrangell economic development director Carol Rushmore says the discovery in Canada brought the redevelopment process of the Institute property to a halt. That’s partly because the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is taking a fresh look at former residential school sites in the United States: the former Wrangell Institute property among them.

“The permit was not issued because of the concerns of cultural resources, perhaps burials on the site,” Rushmore told KSTK in an interview.

U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, an enrolled citizen of the Laguna Pueblo and the first Native American cabinet secretary, ordered a federal investigation of suffering and burials at former BIA schools, with a report due next April.

“They’re looking through the old archives, and many of the records are in boxes, they’re not digitized, they’re having to go through them by hand,” Rushmore explained. “There are issues with privacy act requirements in looking at some of these records, and they’re trying to do consultations with the different tribes, including the WCA, to identify their concerns and information concerning this record search.”

While the federal investigation is more records-based, the Army Corps of Engineers and state Office of Historic Preservation (SHPO) are looking to do an on-the-ground search in Wrangell: “They both will have their own sort of requirements as to what the borough needs to do to make sure that there are no cultural resources on-site,” Rushmore says.

Cooperation with Wrangell’s tribal government is an integral part of the task.

“We’re just happy to be able to work with the city on something of such critical importance and a sad part of the history of our people,” says Esther Reese, whose Tlingit name is Aaltséen. She is the tribal administrator for the Wrangell Cooperative Association. “So it’s very appropriate that the city is working with the tribe on it.”

Reese says the City and Borough of Wrangell has kept the tribe apprised of developments at the property. Earlier this year, the city was looking at possibly using ground-penetrating radar to survey the site.

But: “Because the ground is somewhat uneven, they were looking at bringing in dogs that would help with a search, because it sounded like the radar technology would be more difficult because of the topography,” Reese explained.

In September, Rushmore reported to the borough assembly that the city was drafting a letter to Tribal entities and Native corporations around the state, informing them of Wrangell’s development plans and asking for their input.

With that feedback, Reese says Wrangell’s tribe is starting work on the design for a memorial for Native children from all over the state who attended the Wrangell Institute.

“What the tribe is looking at is consultation with affected tribes and then the construction of a memorial gazebo honoring all the tribes that attended the Institute, then doing a healing ceremony,” Reese says.

Rushmore says at this point, the borough is still trying to contact tribes and figure out how to proceed with a ground search of the property, but nothing is set in stone yet.

Located at a Tlingit site known as Keishangita.’aan, or Alder Top Village, the boarding school opened in 1932. It was not affiliated with a particular religious denomination, although federal records show Wrangell’s Catholic priest in the late 1930s took an interest in the school and incorporated it into his parish.

Reese says the site’s name, Keishangita.’aan, was rediscovered by a tribal citizen in University of Alaska Southeast professor Thomas Thornton’s book “Our Grandparents’ Names on the Land.”

“We let the city know that because we can’t rename something that already had been named by our ancestors,” Reese says, “So that was the name that the tribe brought forward to the city [as a name for the future development].”

The Wrangell Institute was one of about 20 residential schools for Alaska Natives that operated through the 20th century. Its enrollment peaked in the mid-1960s with just over 260 students from five to 15 years old.

The institute housed more than Native children. During World War II in the summer of 1942, Unangax̂ people who were forcibly relocated from their homes stayed in tents on the Institute grounds.

State-collected and individual records recall intense physical, sexual and emotional abuse of Wrangell Institute students. Students were beaten for speaking their first languages, survivors told KSTK in 2016.

So there’s a lot of work — and healing — to do before the property could be redeveloped. In part, that means federal and state surveys. Reese, the tribal administrator, says the borough should be putting out a proposal request for ground surveys soon, possibly with the help of federal funding.

The borough and tribe say they will also continue to collect feedback from tribes and Native organizations around the state whose children were sent to the Wrangell Institute, with the hopes of collecting comments and stories for a memorial that will speak to its history before the ground is repurposed for the future.

This article has been updated to correct the spelling of Esther Reese’s Tlingit name, Aaltséen.

Get in touch with KSTK at news@kstk.org or (907) 874-2345.