Last week (May 6), a crew of researchers set out on a mission to find the wreck of a cannery ship that sank in Southeast Alaska over 100 years ago. But the process of trying to find and identify a shipwreck involves a lot more than just looking in the water.

Thirty years ago, off the jagged cliff shores of Coronation Island in southern Southeast Alaska, Gig Decker and a couple of friends – working with their nonprofit the Southeast Preservation Divers – found an anchor chain about 70 feet underwater.

“When we first ran across the chain, it was obvious on the sounder that we had found it. I mean, it was very, very distinctive,” Decker says. And it wasn’t just any anchor chain: “I felt 89% sure that it was the chain from the [Star of] Bengal.”

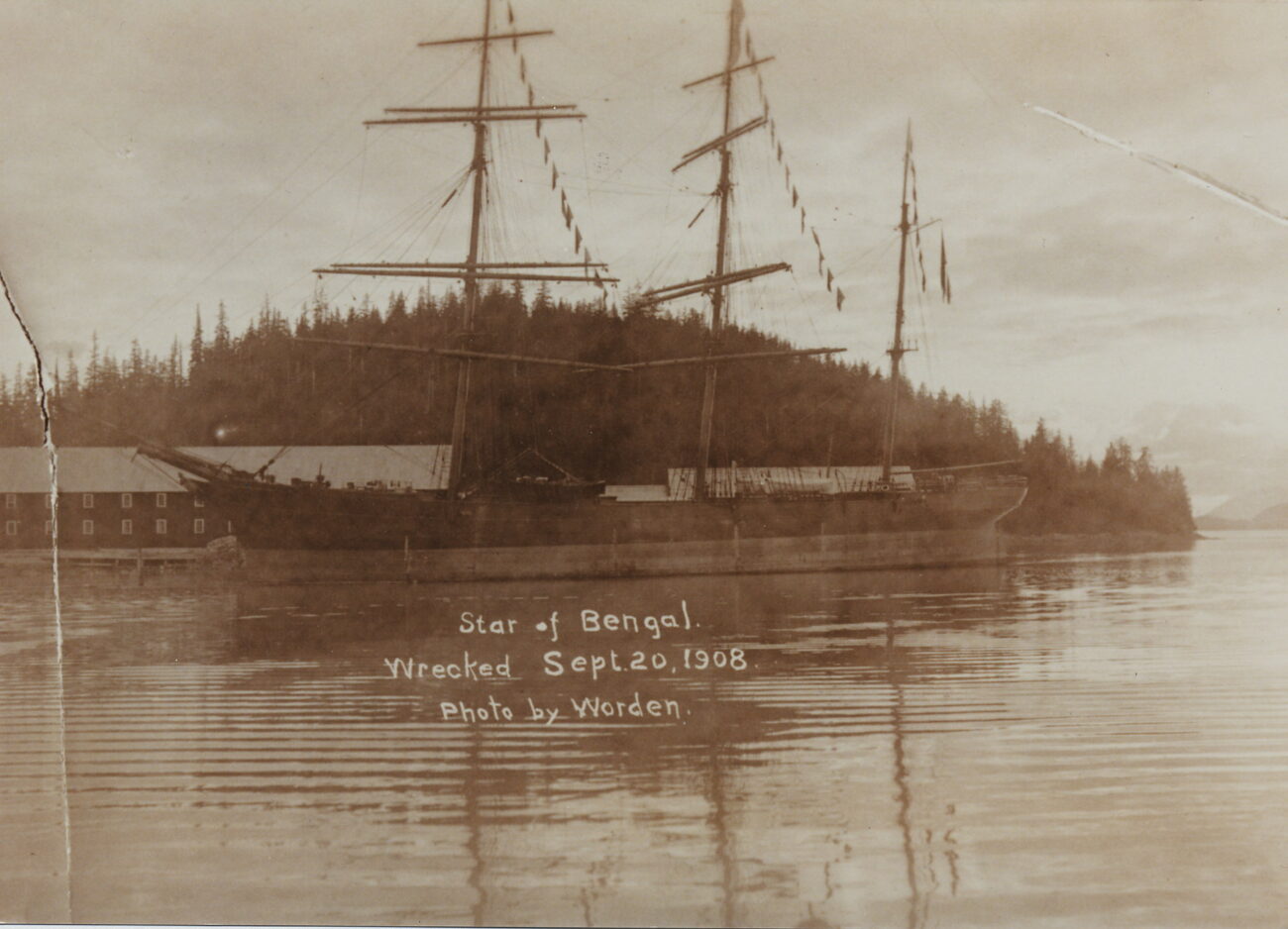

The Star of Bengal was an iron-hulled, 270-foot cannery vessel that went down in a storm in 1908, killing over 100 people. Most of them were cannery workers from China, Japan and the Philippines.

“I went down and had a chance to go to the anchor and then follow the chain to the wreck. I was really happy to be able to be the first one – I thought – in 100 years that had seen it,” Decker says. “It was a huge thrill. I mean, I can only think of a couple of things in my life that really did it for me. And that was definitely one of them.”

Decker and the Southeast Preservation Divers had been searching for the wreck in the hopes of revisiting its history, and registering it as a historic site. Decker says he became interested in shipwreck diving over the course of his 38 years as a commercial harvest diver.

“I had a chance to cover many, many miles of coastline,” Decker says, “ And ran into a variety of wrecks, from ancient wrecks to gillnetters and trollers and sport boats. The whole business of shipwrecks has always really fascinated me, you know, kind of a mysterious thing […] shipwrecks kind of embody a tangible aspect of history, particularly if they are gravesites, which a lot of them are.”

Decker has spent decades researching the Star of Bengal wreck. And while he says he’s almost sure what he saw on the seabed was the Bengal, there’s quite a bit left to do before he can be certain.

“The next step I’ve always known is to get out there with a bottom mapping system to where we can do a 3-D model of the wreck itself, the cove and the entry to it. And then most importantly, having a state-certified underwater archaeologist out there to claim that it was, in fact, the [Star of] Bengal,” Decker says. “After that, we can go on for a larger investigation of the wreck.”

(Sage Smiley / KSTK)

That process started May 6, as an eight-person research crew set out from Wrangell aboard the Alaska Endeavour and headed for the site of the wreck.

That includes Decker, marine archaeologist Jenya Anichenko, writer and visual artist Tessa Hulls, artist and musician Ray Troll, researcher Shawn Dilles, remote sensing specialist Sean Adams, and Endeavour owners Patsy Clark Urschel and Bill Urschel.

Part of their investigation aims to pinpoint where precisely the wreck is located. Decker dove what he believed to be the site more than 30 years ago, and didn’t have GPS mapping.

This time, they’re taking a more high-tech approach. Sean Adams is in charge of the expedition’s arsenal of sonar equipment, aerial drones, and a device known as a magnetometer, which senses iron – useful when looking for an iron ship.

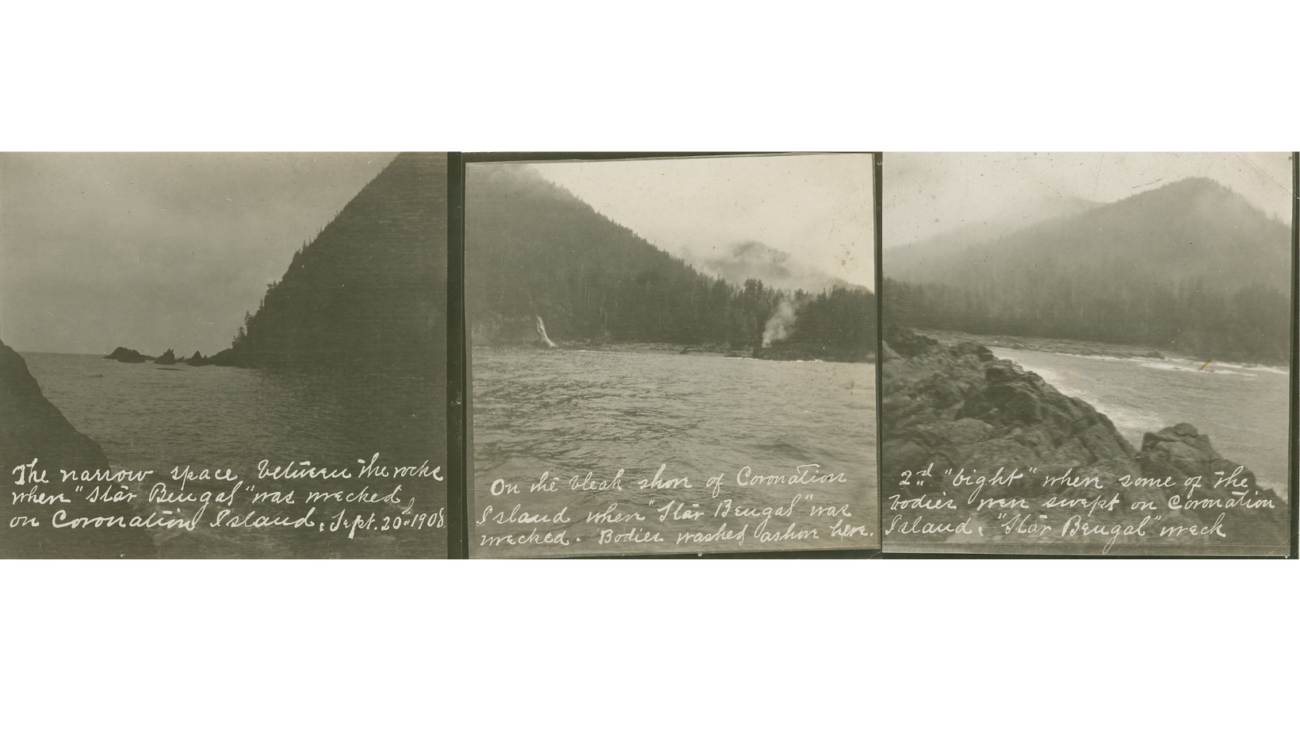

“It’s the perfect target for the magnetometer,” Adams told the expedition crew on May 5. Before leaving on their expedition, some of the team stopped by Wrangell’s museum to look at photos that seem to have been taken by the party sent to bury bodies after the Bengal went down in 1908.

“So, can you just cruise through and send out the gizmos? Boom, there’s the ship. Is it gonna be easy?” asked Ketchikan-based artist Ray Troll.

“It…” Adams laughed, “Is very complicated.”

The magnetometer is light enough to be mounted on a drone, and flown in a grid to try and sense the location of a wreck like the Bengal. Adams says it’s typically used for detecting unexploded bombs or artillery shells buried under the ground. In this case, he’s hoping it could point the crew in the general direction of the wreck.

“You’re not going to get as detailed or a high definition targets and the smaller targets are not going to show up as well,” Adams explains, “But it seems to be a very good magnetometer. This is kind of a new use for it – an experimental test.”

But the crew isn’t just relying on high-tech gadgets to locate the lost ship. They’re also turning to the historical record. Researcher Shawn Dilles says he’s looked all over the country for photos of the Star of Bengal and the site of its wreck like the ones in the collection of the Wrangell Museum, housed in the Nolan Center.

“I think the Nolan Center played a critical role in this,” Dilles said. “I’ve looked in archives all over the country and seen some of these photos, but not those two critical photos. We still don’t know exactly who took them and what day, but it’s a very reasonable guess, I think, to think it was a week after or so – within a week of the wreck and taken by the burial party.”

(Photos courtesy of The Wrangell Museum)

The collection of tiny, square black and white photos with white cursive writing seems to indicate one of two coves along the southern coast of Coronation Island could be the site of the wreck.

“That’s what makes this a mystery is that we have two lines of evidence, and neither can be eliminated,” Dilles said while examining the photos in the Nolan Center office. “It’s not about right and wrong.”

For Decker, the commercial diver who thinks he found the Bengal three decades ago, the search is not just about finding a sunken ship. It’s about correcting the historical record.

“Those [cannery workers,] we can’t bring them back, but we can get the story straight that they didn’t die in the hold because they were hiding,” Decker says. “They were very courageous people to put themselves in the position they did. And they were murdered by cowardice.”

The crew of the Alaska Endeavour will host a webinar to share some of their research and the results of their explorations on Friday, May 13 at 9 a.m. Alaska time. Find a link at alaskaendeavour.org.

Get in touch with KSTK at news@kstk.org or (907) 874-2345.