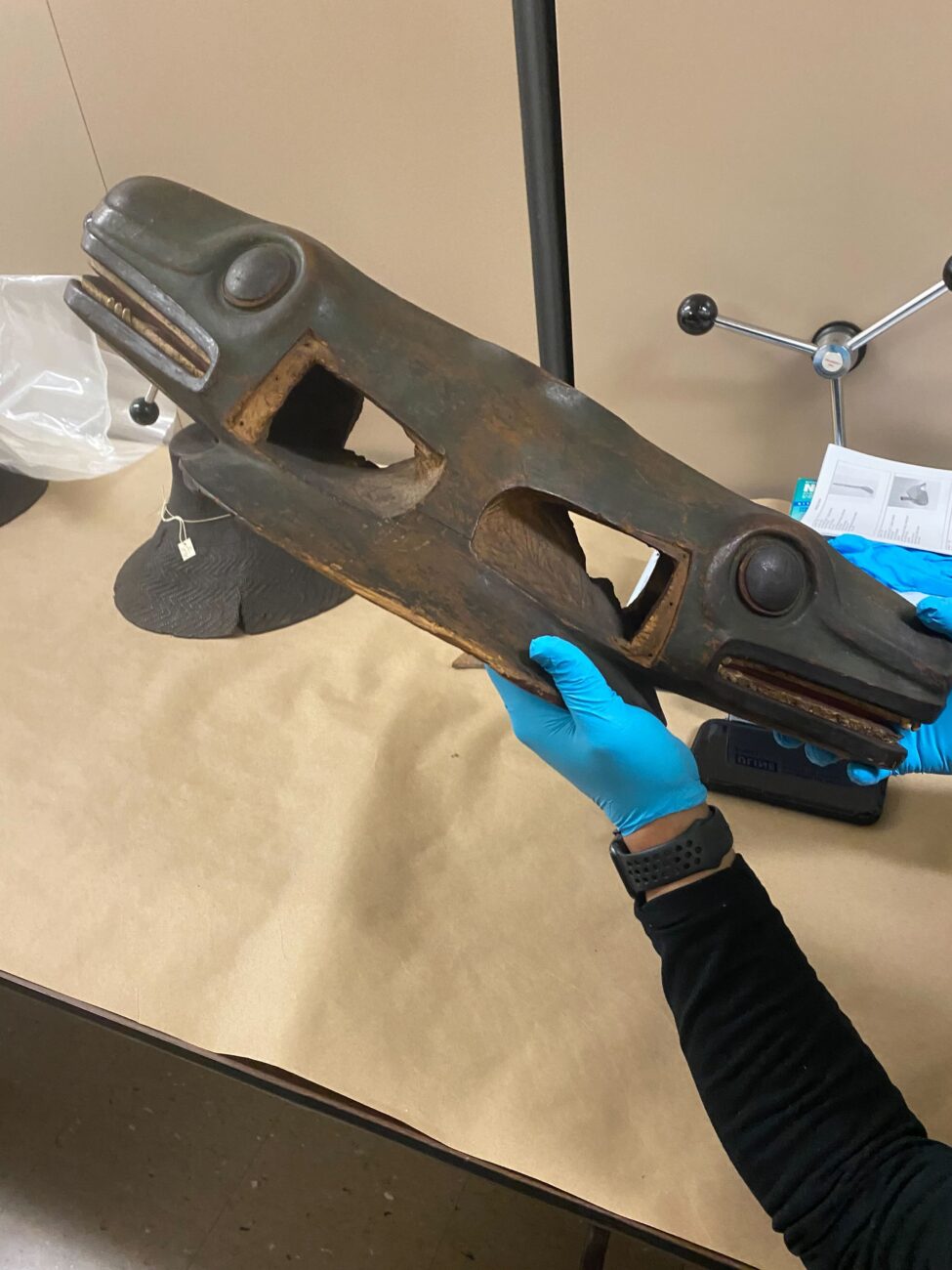

(Sage Smiley / KSTK)

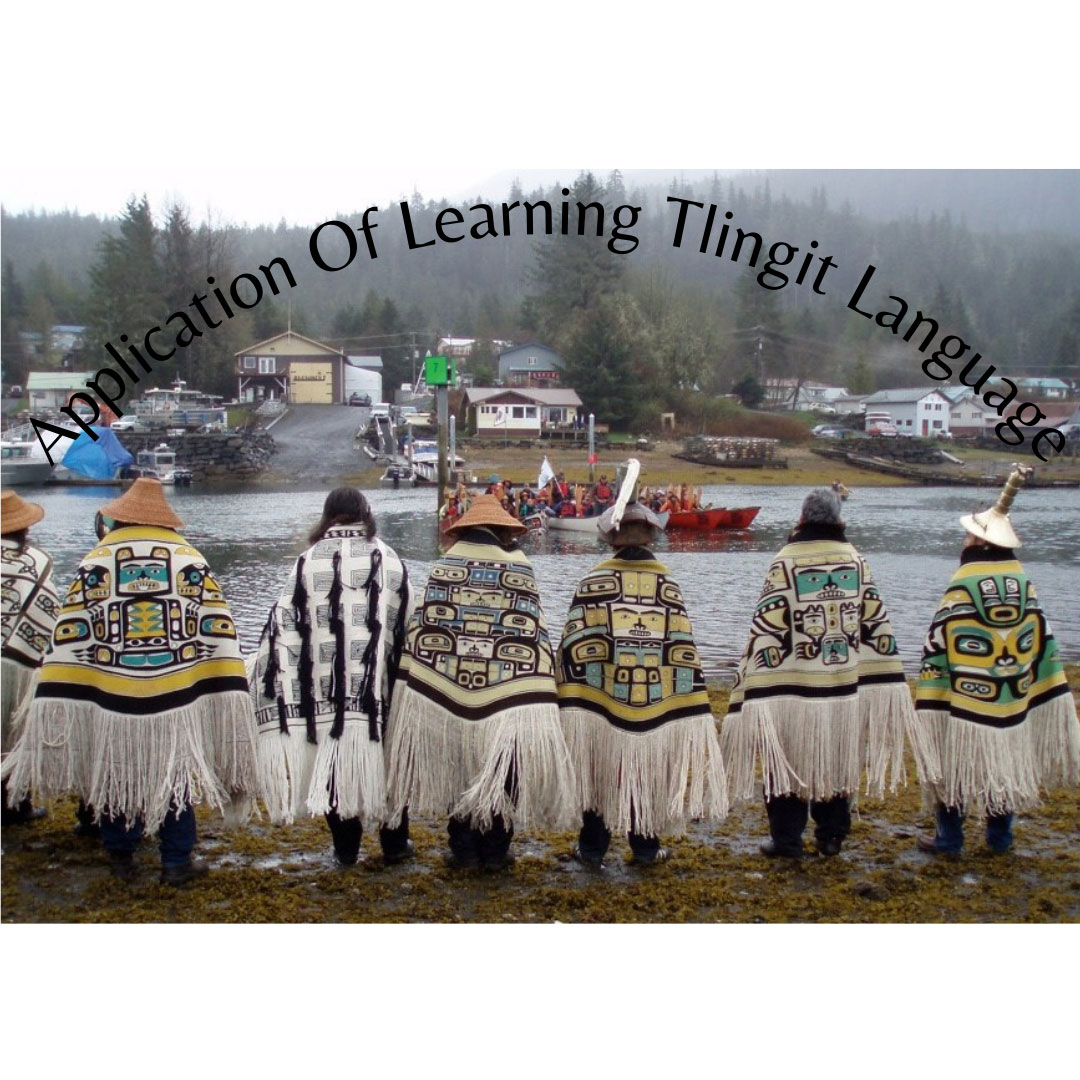

In recent years, more than two dozen at.óow, or Lingít clan property items have been repatriated to Wrangell clans. But hundreds more still sit in collections of museums throughout the world. KSTK reports on the ongoing efforts to bring sacred clan property home.

View the video described in this article at the bottom of the page.

A man, Kevin T’aawyaat Callahan, crouches, swings his head, and growls through a wooden vocal magnifier in the small round doorway of Wrangell’s Chief Shakes Tribal House.

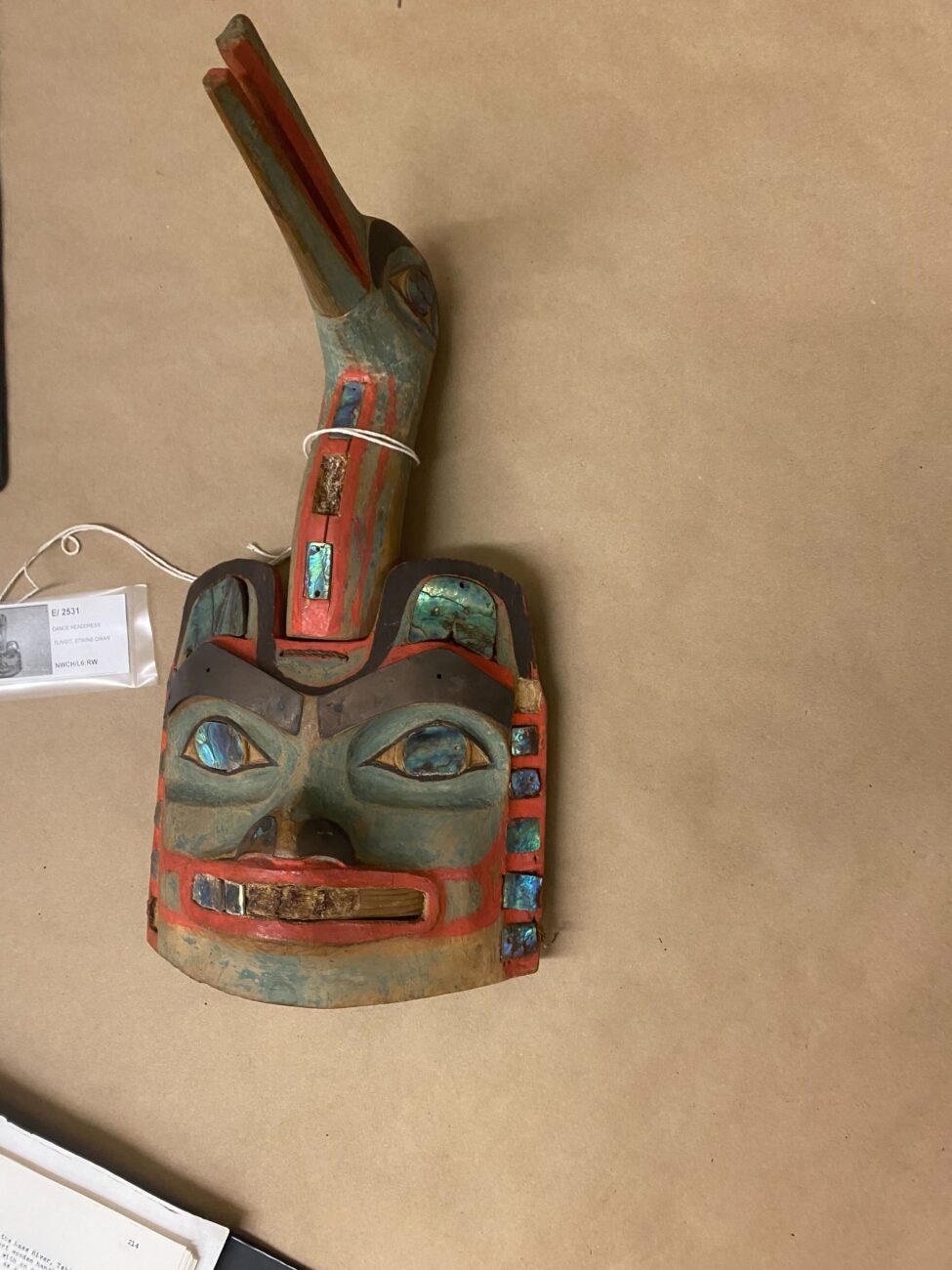

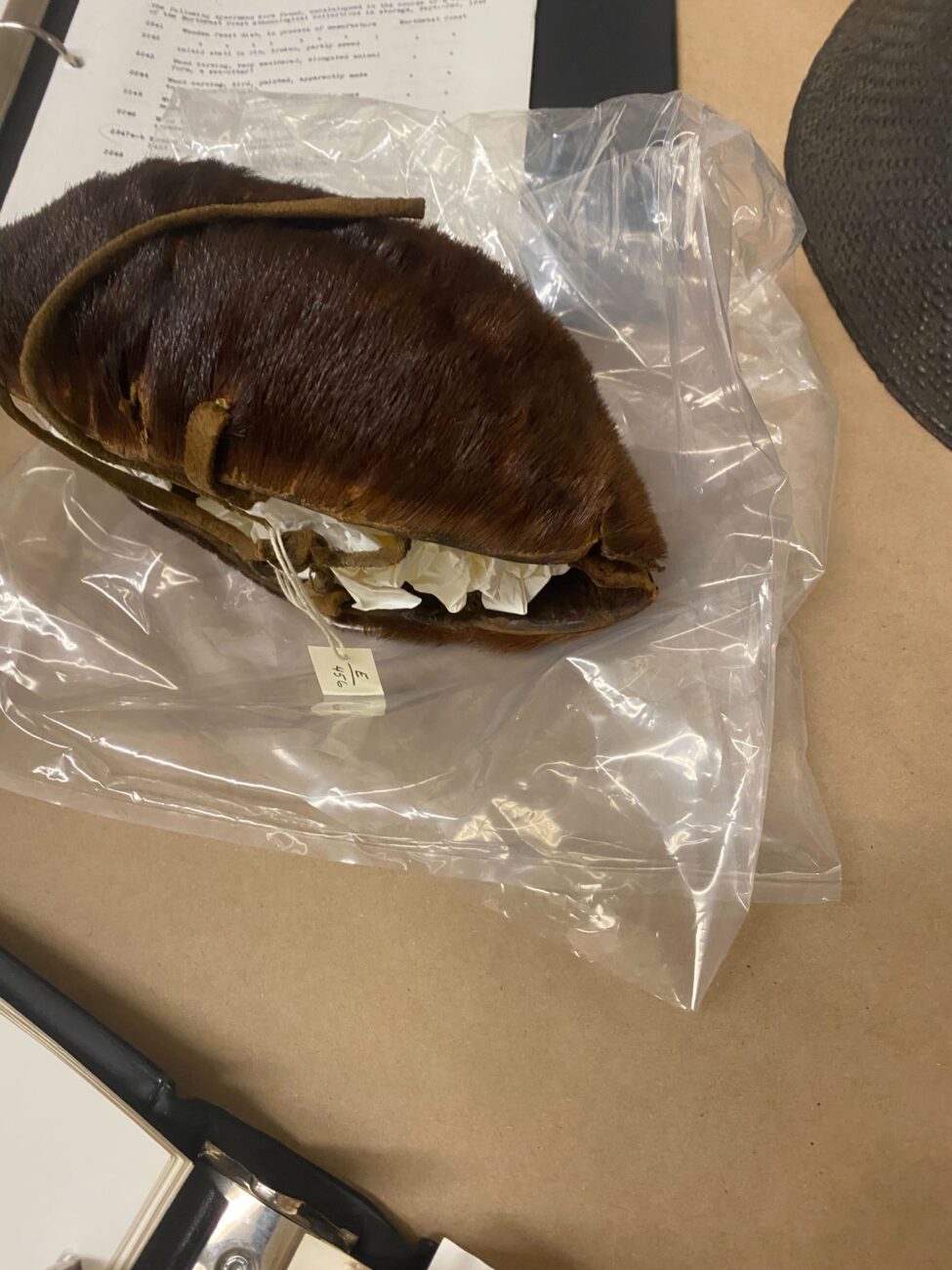

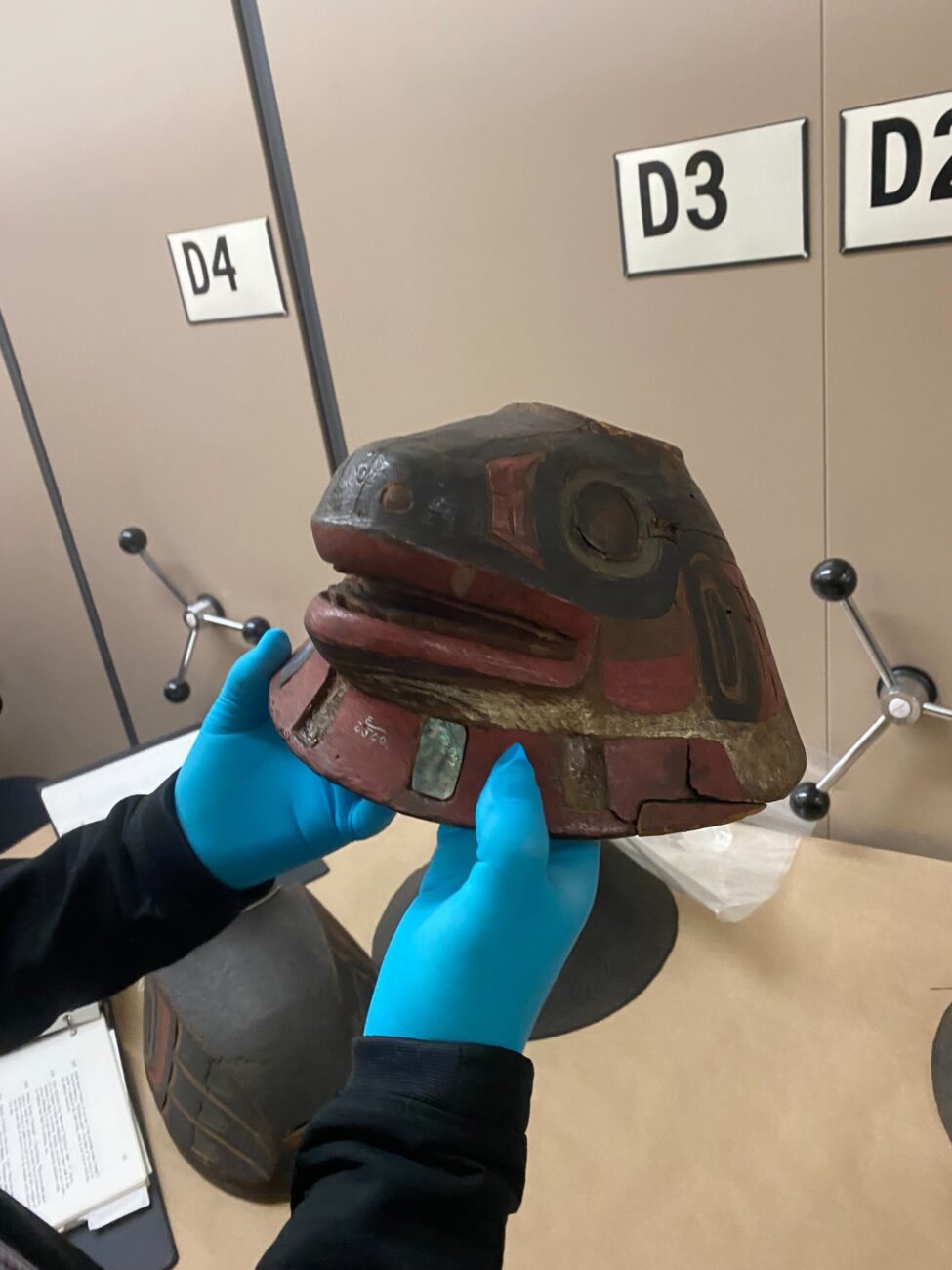

He wears a grizzly bear mask, Xoots L’axkeit, one of the two-dozen items returned to Wrangell clans in recent years from museums across the Western U.S. – the Burke Museum in Seattle, the Portland Art Museum, the Denver Art Museum and others.

His performance was part of a celebration, a ku.éex’, to welcome the items home to the Naanya.aayí that took place in early September. Vydell Baker, L’uknax̱.ádi dachx̱án (grandchild of the L’uknax̱.ádi) filmed the scene and shared it with KSTK.

Some of the returned items were part of a large collection amassed by former Wrangell educator Axel Rasmussen. Four items had been seized from homes by Wrangell police in the 1930s.

Repatriation is a slow and ongoing process. Museums from coast to coast hold at.óow – clan property – of Wrangell clans, including human remains.

Returns are facilitated through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), a 1990 law aimed at returning and protecting Native remains, funerary objects, and sacred objects of cultural patrimony.

“I wish it was faster,” said Harold Jacobs, a repatriation specialist with the regional tribal government, the Central Council of Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska. The tribe has received hundreds of thousands of dollars of federal support in recent years to help facilitate clan item repatriations.

“Federal law says they have 90 days to respond to a claim,” Jacobs said during an interview last summer. But often the process stretches years-long.

Last year, the Portland Art Museum returned nine clan objects to Wrangell’s Naanya.aayí, which were taken from them in the 1940s by the former superintendent of schools Axel Rasmussen, who also served as superintendent in Skagway.

“The last two years, of course, the pandemic held it up,” Jacobs said. “They were ready to come back then but we couldn’t do any travel with either institution – the tribe or the museum – because of travel restrictions.”

Jacobs said Tlingit & Haida asked for the items back in 2002 – 20 years before they returned to the Naanya.aayí.

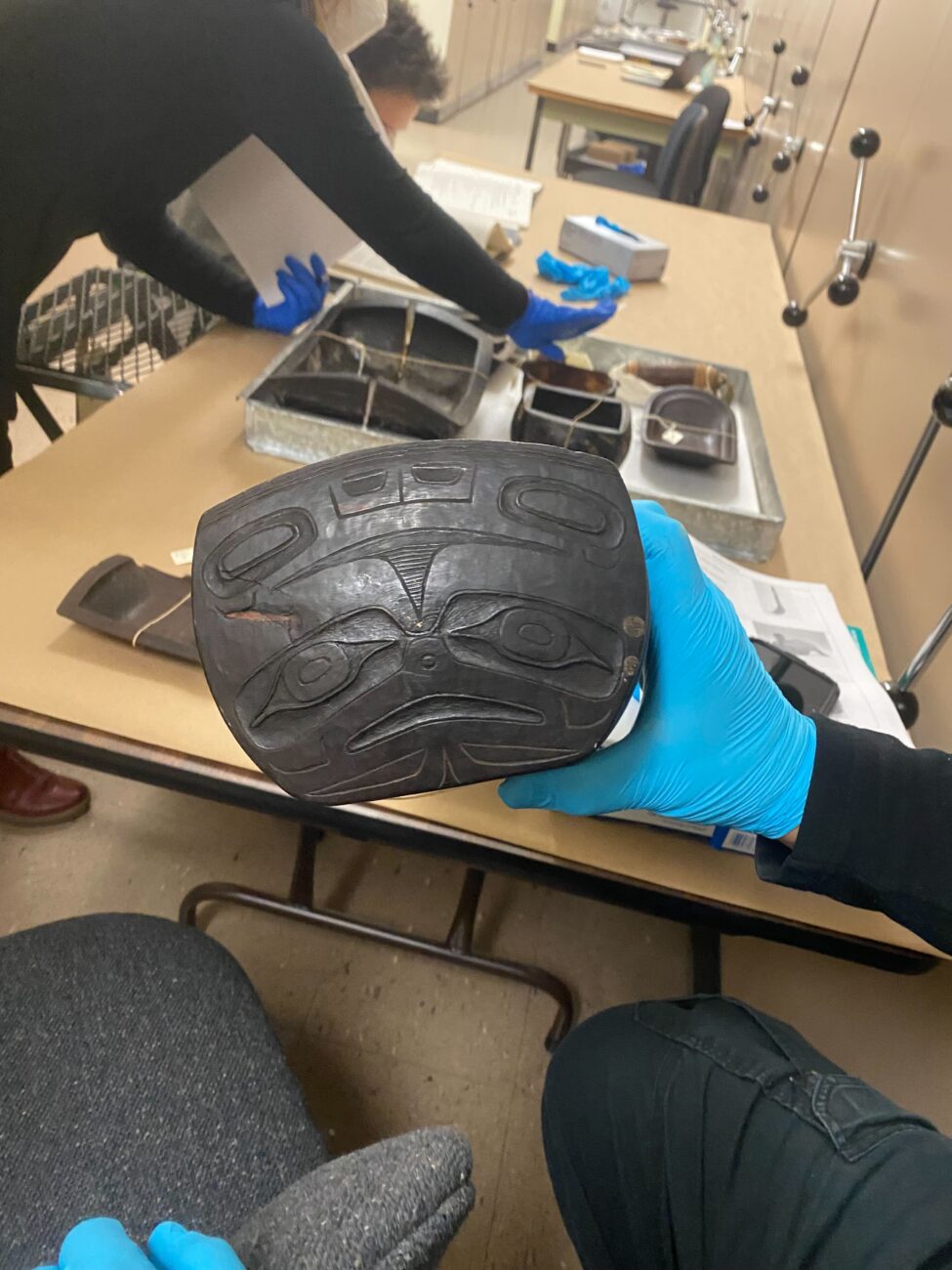

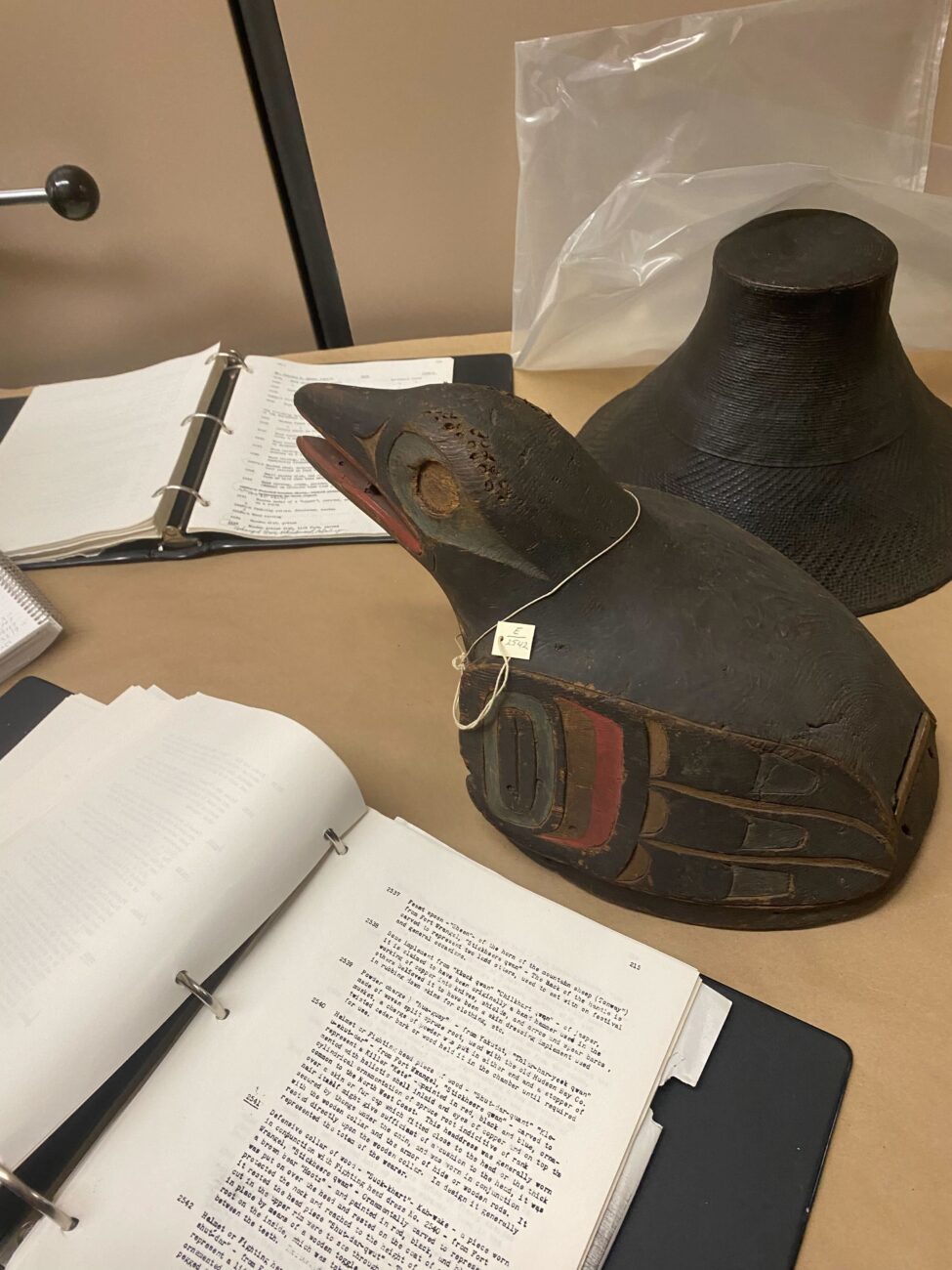

Clan members used some of the objects – which included Killerwhale and Mudshark hats, Killerwhale robes, Mudshark shirts, and a Storm headdress – to lead dances at Celebration 2022, the biennial festival of Lingít, Haida and Tsimshian cultures.

Many other repatriations are in process. In early March, a museum in Maine published its intent to repatriate a Kiks.ádi clan helmet taken from Wrangell at an unknown date. That intent to repatriate came after representatives from the Central Council visited the museum in 2018.

Xúns Richard Oliver is a former tribal president for the Wrangell Cooperative Association, of the Kayaashkeiditaan clan.

“An item that belongs to the clan belongs to the whole clan. And it’s supposed to remain with that clan,” Oliver said during an interview at the Wrangell Cooperative Association’s Cultural Center in early March. Some items were lost or sold because of cultural lineage – Lingít people are from one of two moieties: Yeil (Raven) and Ch’aak / Gooch (Eagle / Wolf).

“Sometimes a person will die, and then the opposite will end up with it because an Eagle marries a Raven,” Oliver explained. “And then all of a sudden these clan possessions are in the hands of a Raven, and they should be passed down to the Eagle and so that they remain in the clan they’re supposed to be in. So that’s how [we] will explain it to the museum and put in a claim.”

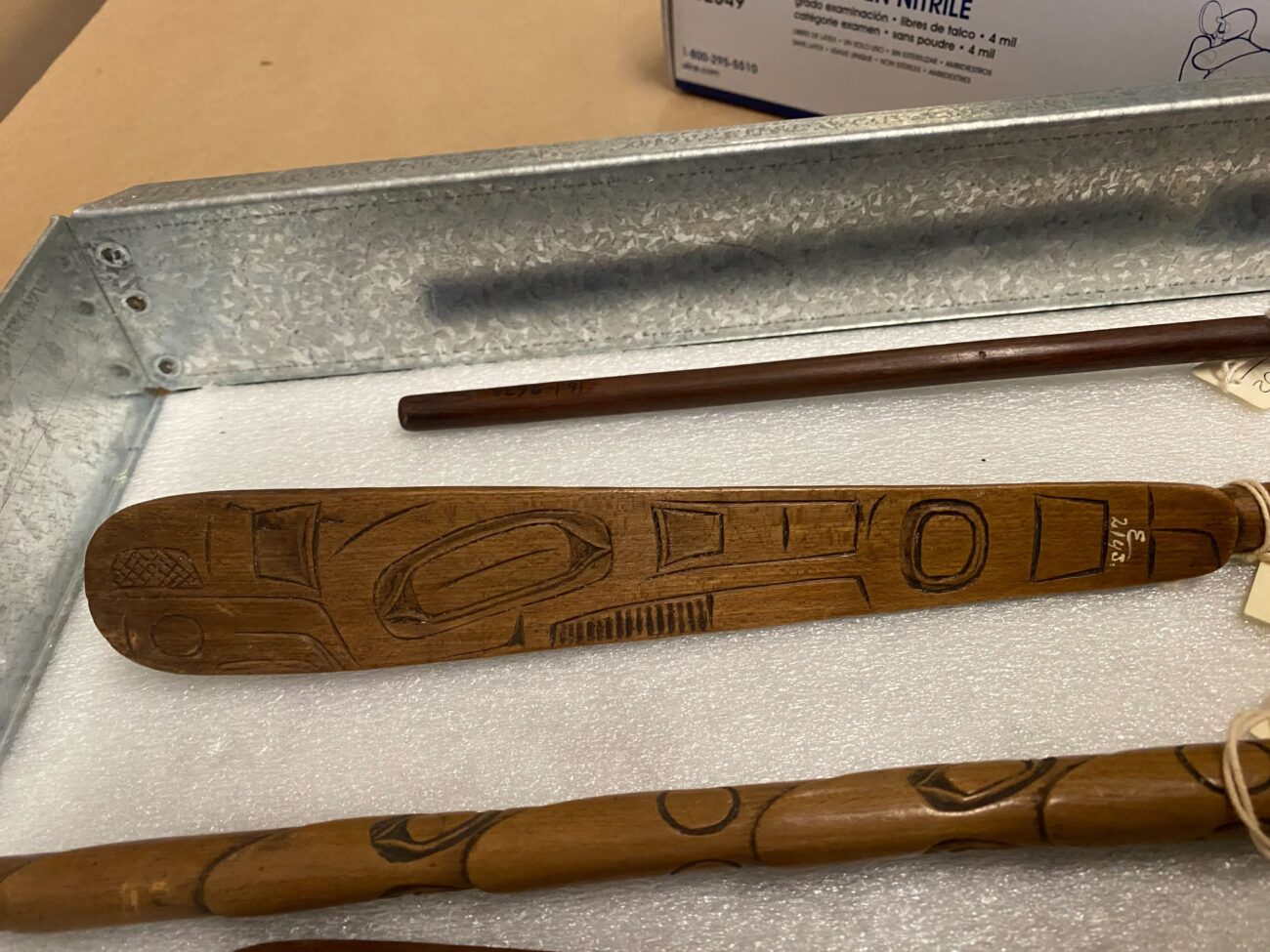

Earlier this year, Oliver traveled with Harold Jacobs and others to New York City to see more than 100 Wrangell clan items in the Museum of Natural History and the Museum of the American Indian.

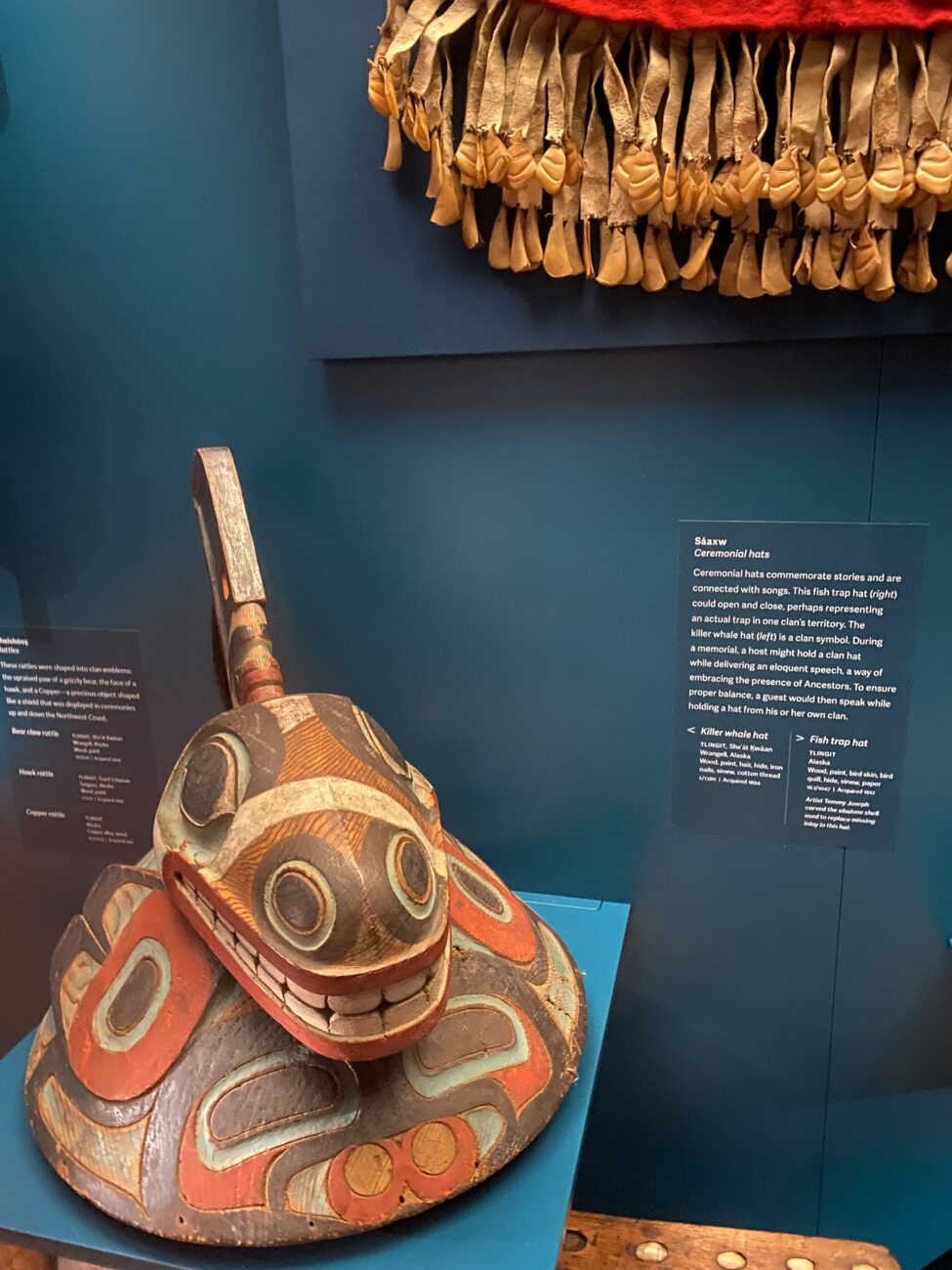

(Courtesy Richard Oliver)

“Some of them, we don’t know which clan they belong to, but we do know they came from Wrangell,” Oliver said, speaking of the items he viewed. “Some are the Naanya.aayí possessions, Chief Shakes. Also, some are Kayaashkeiditaan we know of. But the rest was from the Emmons expedition when they came through here, and they didn’t have any rights to them. Some of them are shaman objects that were just taken right off of the graves.”

Oliver expanded on the Kayaashkeiditaan items: “For my clan, the ones that they did know, were two large serving platters that were about three foot wide by about one and a half foot deep and very ornate carvings on them and shells and we know that they belong to the Kayaashkeiditaan. Also, at one of the museums we went to, Chief Shakes [Naanya.aayí clan leader] has a dagger there and speaker staff, which they know belongs to the Chief. So we’re really interested in getting those back.”

Oliver said he asked repatriation specialist Harold Jacobs about bringing back petroglyphs that were taken from Etolin Island, just west of Wrangell, as well, “And he said he’s never repatriated a petroglyph before because it’s hard to prove what clan they came from. But I told him: ‘You know, to me if it was next to a salmon stream, it belongs to the clam that had that salmon stream.’ And he agreed.”

That proving of clan ownership is an important part of the repatriation process – but that can be tough when items are ancient.

Kathleen Ash-Milby is the curator of Native American Art at the Portland Art Museum and an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation. She oversaw the return of the nine Naanya.aayí at.óow in the spring of 2022.

“It’s really incumbent upon the tribe to explain and present the case – in this case, it was primarily oral histories, and stories and songs about the objects and the relationship to the clans and the crests that were depicted on the items, it shows that they belong to this particular group,” Ash-Milby explained in a July 2022 interview. “This case was actually kind of exceptional, in a way, because there was actually photographic documentation going back to the late 19th century that showed the items as clan property. And that was actually really kind of exciting to be able to see the objects in their original context.”

Museums are colonial institutions, Ash-Milby said. Museums were often formed out of the collections of private individuals who had acquired paintings, ceramics, or Native American cultural material.

“There’s definitely been historically a lot of tension between Native communities and museums because museums had a mandate to hold this material,” Ash-Milby said, “and I think that the way that museums operate and the way that they see their collections has really changed in the last 100 years. I’d say it’s even changed quite a bit in the last 30 years.”

Ash-Milby said museums like the Portland Art Museum take dispossessions seriously but are working to shift the historical relationship with tribes.

“NAGPRA definitely has been a huge help in, I would say, in shoving forward that relationship-building,” she said. “I think it was already happening in some cases. But I think that having that federal law has really motivated museums to think more carefully about their relationships with Native communities and how they care for these objects. And also realigning their thinking about these objects as being something purely from the past, and not something that’s part of a living culture.”

That living culture is an important reason to pursue repatriation for Oliver, the former Wrangell tribal president.

“It’s bringing back the culture and things that were forgotten,” Oliver said. “We would like to – some of these are priceless items that you wouldn’t use, but you could use it to carve more of them. And in Wrangell, people need to learn how to carve. We don’t have any master carvers here. We have this cultural center, and we would like to get carving again, bring it back to Wrangell.”

He said the objects should be seen, appreciated, and enjoyed.

“We have a beautiful museum that really should be filled with the things that belong here,” Oliver said. “If we have to try to build another wing to fit all these things, that would be a good thing too.”

Wrangell’s museum, housed at the borough-owned Nolan Center, has limited space but is working on a grant for a new display case. Tribal council members have publicly expressed concern about storage and discussed the possibility of building another museum to house repatriated Wrangell at.óow, and those that come come in the future.

11/1: This article has been updated to correct a statement. Wrangell’s Nolan Center and museum have climate controls.

Get in touch with KSTK at news@kstk.org or (907) 874-2345.