A group of fifth grade students ask questions to four Wrangell High School students who had the privilege of processing a seal this past Monday with elder Henry Larsen.

One of the fifth graders ask, “What is that?”

“That’s part of the backstrap,” Larsen replied.

Everyone’s gathered around the seal in the home economics classroom. They’re visiting the classroom to see how the four high school students are processing it for an oceanography lab intensive. It’s part of a dual credit course for high school students that incorporates culture and science.

The young students were listening to Larsen talk about traditional seal hunting. He grew up in Sitka and Petersburg, but lives in Juneau now. Larsen harvested this seal that morning for the class.

He sews the pelts into wallets, headbands, pillows, scarves and earrings – skills he learned as a young boy.

“I’ve been sewing since 1964,” Larsen said. “My grandmother taught me how to sew.”

One fifth grader points out the blood on the fur sitting in a cooler and asked how to clean it.

“I use soap, Dawn soap, and a brush and get all the fat and oil off of it,” Larsen said. “So as a skin sewer, I want my material to look like her earrings. A lot of the times people won’t clean them like that so they turn yellow.”

“…that’ll be in their heads forever.”

Larsen said they’re processing every part of the seal, from the head to the flippers. Sealaska Heritage Institute contracted him to harvest it for the class and share his knowledge.

“Coming here to the school and teaching, showing the younger kids to get involved with some of the hunt, or what the animal looks like when the hide’s off or anything, that’ll be in their heads forever,” he said. “Then they’ll be like, ‘Oh, I want to start doing that.'”

For him, spending time with students is about passing down knowledge so the culture continues on.

“I’m just glad these young people, like Jackson, is here,” Larsen said. “He’s wanting to see what the animal looks like. He’s not able to shoot one, but he’s always wanted to see it. That means a lot to me. He’s willing to learn that.”

Ocean as Teacher

He’s talking about junior Jackson Carney, one of the four students in this environmental science course called Ocean as Teacher.

“It’s really cool to get the experience to see a seal getting processed like this,” he said. “It’s just knowledge that not everyone gets to see, not something everyone gets to experience.”

He said the group removed the hide first, then processed everything else. They even boiled the vertebrae. He said the first thing he noticed was how dark the meat is.

The seal’s features can be eye opening

“It’s because of the amount of oxygen they need to have in their muscles so they can dive deeper and hold their breath longer,” Carney said. “It’s an offset between hemoglobin and myoglobin, that’s what causes it to be so dark.”

Carney said he was also surprised by the seal’s features – the large, completely dilated black eyes, adapted for deep water, and the claws hidden in their fins.

“When they’re swimming, they’re just tucked away,” he said. “But when they go on rocks, they can go on their tippy toes and then their claws stick into the rock. It’s pretty sweet.”

“…[students] have access to Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian knowledge holders…”

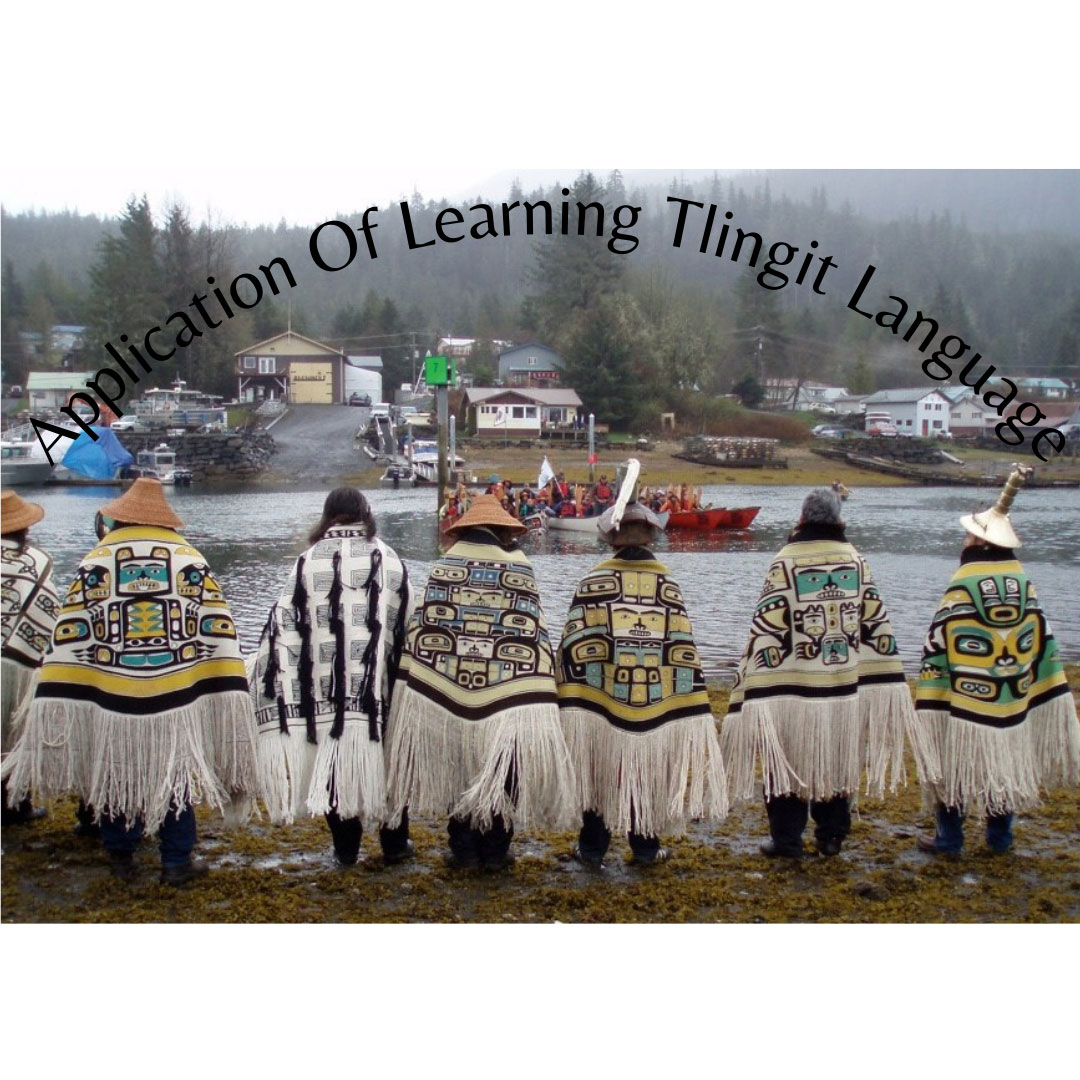

The oceanography course is a collaboration between University of Alaska Southeast, Sealaska Heritage Institute and five partner communities in Southeast Alaska: Wrangell, Angoon, Sitka, Juneau and Kake. SHI funds the $9 million grant, aiming to integrate Indigenous science into STEAM education. STEAM stands for science, technology, engineering, art and mathematics.

“We also hire cultural specialists, and so they [students] have access to Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian knowledge holders to guide them in their lessons for appropriate incorporation of our cultures,” SHI’s STEAM Pathways Grant Manager Krissa Huston said.

She said there is a shift in acknowledging Indigenous science so students can build real pathways forward using it.

“I never had these opportunities as a Lingít student growing up in Southeast,” Huston said. “But having the opportunity to have students use immersive technology, such as environmental DNA analysis with traditional harvesting and processing is so memorable, and that is the core of this work that really gets me excited about this job.”

Bridging traditional knowledge with Western oceanographic knowledge

Bridgette Reynolds is the co-adjunct instructor of the dual enrollment environmental science course at the university.

“We developed this course to bridge traditional knowledge with what we consider Western oceanographic knowledge,” she said. “So we’ve been doing lots of different topics focused on the physical characteristics of the ocean, and then combining those with traditional stories and Indigenous science.”

She said this particular oceanography class helps students see why seal hunting remains vital for Southeast Alaska Indigenous people.

“…full of so much understanding of place and so much connection…”

“Some people are like, ‘Oh, that’s not science,’” Reynolds said. “But again, actually it is full of so much understanding of place and so much connection to the world here in southeast Alaska.”

Reynolds said this is the third year this course is offered, rewritten as a college level course and accessible to partner communities through travel labs. In the spring they offer the introductory course to the dual enrollment environmental science pathway called Canoe Forest.

She said all the seal meat from today’s lesson will be distributed through the local tribe, Wrangell Cooperative Association.